Really simple distributed DNS

There is a project, originating within the CCC, to link hackerspaces around the world into a common VPN. Within this, we would like to provide DNS; probably under a fake TLD, say .hack. Well, you know, we like decentralized systems… This post is about a prototype distributed system that, give or take a few design iterations, could actually be useful for decentralized name resolution. Desirable properties:- require only a minimum of local knowledge to configure the peers

- distributed self-organization instead of central administration

- avoid central points of failure

ontowith the expectation that all entities also

on the mediumwill receive them. Concretely there are two kinds of nodes:

- Low-level network links. IP-port pairs or other kinds of peer-to-peer addresses. The idea is that these could also be Ethernet interfaces and thelike. They carry no global name and are thought of as only locally known to a specific station (host system).

Mesh

nodes (for lack of a better name). Formed by connecting stations in a mesh. Has a globally unique ID. For each node it participates in, a station knows how to reach its neighbors within that node. Any other node known to the station can act as the medium for these connections. Putting other meshes in this list effectively creates a tunnel.

- Payload. In the example code, these consist of a single String containing a message to be printed.

- Tunnel messages. When a message is sent onto a mesh node, the station wraps it with the ID of that node before sending it down the neighbor links (i.e. nodes).

unwrappingthe tunneling headers and propagates the message to any neighbors it has within the respective nodes. Given the above behaviour, it is possible to construct networks of nodes interconnected in rather arbitrary ways. For the purpose of emulating DNS, and probably many others, it is useful to think of nodes as either representing hosts or being formed by joining (

federating) a number of subnodes. The federations would correspond to DNS domains. Determining how each station's table of node neighbor connections should look is left as an exercise to the reader. ;) The attached code contains a number of such context tables for an example network, pictured below.

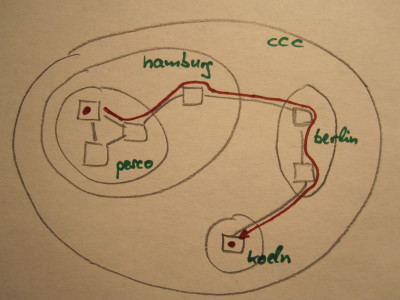

Diagram of a hypothetical network showing

federations (circles with green labels), hosts (squares), and

low-level links (lines).

Shown in red is the path of an example message

from within a hamburg subnode to a host in cologne.

$ ghc rsddns-proto.hs -e 'mainloop 2001 laptop_ct'

$ ghc rsddns-proto.hs -e 'mainloop 2002 daddel_ct'

$ ghc rsddns-proto.hs -e 'mainloop 2003 router_ct'

$ ghc rsddns-proto.hs -e 'mainloop 2004 turing_ct'

$ ghc rsddns-proto.hs -e 'mainloop 2005 b1_ct'

$ ghc rsddns-proto.hs -e 'mainloop 2006 b2_ct'

$ ghc rsddns-proto.hs -e 'mainloop 2007 k1_ct'

$ ghci rsddns-proto.hs

> s <- testsocket 5555

> testsend s "127.0.0.1" 2001 $ Mtun "pesco.hh.ccc.hack" $

Mtun "hh.ccc.hack" $ Mtun "ccc.hack" $ Mtun "koeln.ccc.hack" $

Mtun "k1.koeln.ccc.hack" $ Mstr "hello world!"